Ireland 3000: Drawing with the Jigsaw

“I will find most enjoyment in a line I have captured, the curve of a finger or the bend of a knee.”

Be honest, laugh as you make work, accept mysteries, make good decisions, push forward, and learn from difficulties. This is the ethos behind Ireland 3000’s practice.

Drawing Pöx: You use a saw, and at its core, your process feels like drawing. What attracts you to it?

Ireland 3000: My process was developed over the course of two years, through many experiments and failures. The desire was to create large-scale figures, moving beyond the scale limitations of a printing press or bed. This is why I hand-print all my works using a modified ball-bearing baren.

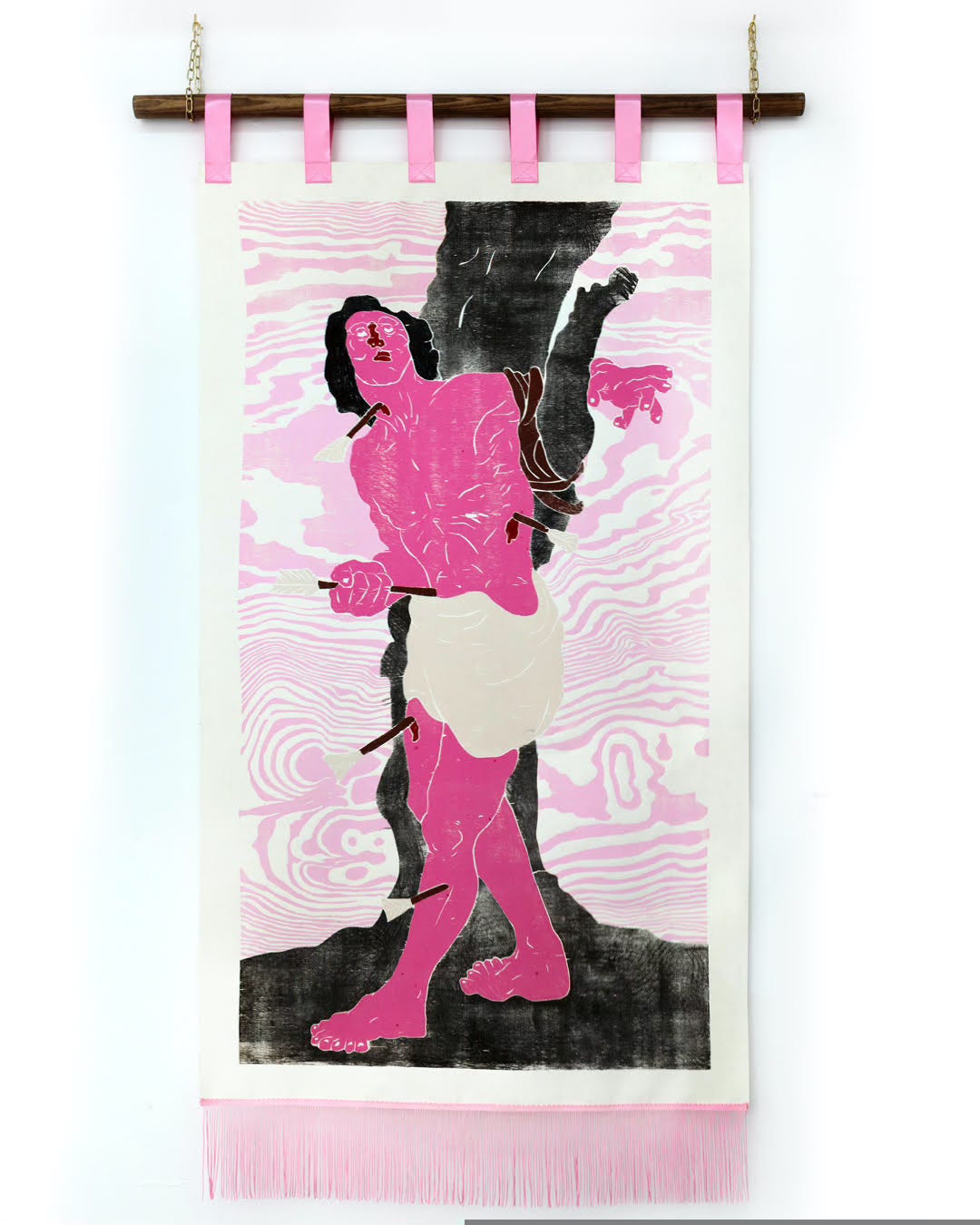

The use of the jigsaw power tool to cut out the figures and shapes is key to the work. The limitations and qualities of drawing with an electric saw give the work a unique energy.

The manipulation of the saw, the confidence required in your line, and the lack of a second chance all add to the qualities of the work and the fun I have making it.

Drawing Pöx: You took the structure and visual drama of Caravaggio’s Entombment of Christ and reworked it through your own method. What was your intuition?

This body of work began with Caravaggio’s painting “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas”. I loved this image and the weird bizarreness of Christian imagery. When I re-created this painting as a woodblock, I realised the potential to explore Christian imagery within my process.

Re-creating these works allowed me to reflect on our inherited Christian morality, the role of the artist, and the importance of originality in art-making. It also gave me space to focus on drawing the bodies and robes, and to bring in more low-brow influences through cartoonish colours and exaggerated elements.

This piece, “The Entombment of Christ”, contains all of these ideas but it could also just be some people who’ve fallen out of a pub drunk at closing time, carrying their friend.

Drawing Pöx: There is a particular, and very similar, energy when you talk about wood and when you talk about the human body. What is it that draws you to them, and what connects the two for you?

I’ve always worked with the body as the vehicle to express myself since I began making art. Drawing and the body are constants within my practice, but the medium has changed over the years. It started with printmaking, then wooden sculptures, moved into performance art, and now has returned to printmaking. Making these woodcuts feels like a nice combination of all my previous work, but funnily what seems so obvious now took me some years to find.

The mediums have changed over time, but I’m always drawn to physicality, action, and the realness of a material. I use the cheapest large wooden sheets I can get from the building supply store. They have the roughest grain with the most imperfections, and I really like the surprises that appear when you print the wood. I often find when I’m drawing and cutting the wood, if I can make myself laugh, it’s been quite successful.

An art practice is a strange thing to carry with you through life, and there are always mysteries within it. I’m just happy if my practice continues to challenge me.

Right now, I’m planning a series of landscape prints, which I’m really excited about.

Drawing Pöx: Mysteries within your practice - can you describe one you are currently sitting with?

I’m really lucky at the moment; I have a lot of clarity in my practice, what I want to do, and what the work is doing. Sometime around 2013, I saw Bill Drummond (KLF) give an artist talk in Glasgow. He talked about not making art bigger than himself and how he was just making paintings that were around 6ft and could fit on top of his Land Rover. This is the artist who in the 90s burned a million pounds on the Scottish island of Jura.

The contradiction in ideas resonated with me and how to think about being an artist. I think it’s important to demystify the creative process, how to be an artist, and how to make work, but also accept the mysteries within the work and not try to pin them down.

Drawing Pöx: In demystifying the creative process, you challenge the assumption of the tormented, conflicted artist by emphasizing that a healthy mind is an artist’s most important tool.

That’s a tricky one. What you say, I believe, is correct regarding a healthy, responsive mind for a prolonged creative practice.

For me, it’s about getting to the studio and making some work. Everything is clearer in the doing.

Once the work is made, it’s editing time: being honest, making good decisions, and keeping pushing.

Drawing Pöx: What is a risk you haven’t taken yet but might be getting closer to?

Around 2012 in Scotland I spent some years doing performance art. I was tired of white cube spaces and wanted to challenge myself and my work. I created a fictional society of nude historical re-enactors - The Edinburgh Nude Historical Society. They would re-enact historical and political events in public spaces. The practice was very challenging and really brought me to my limits but also gave me an understanding of my artistic self and where I could push myself to in service of an idea.

So to think about risks in a more traditional studio practice feels strange, I have places I want to go with the work but I don’t see it as risks - just need the time to get there.

I do a little street art, specifically wheat-pasting, that gives me a more traditional adrenaline rush and risk I need.

Drawing Pöx: You mentioned a new series of landscape prints. What makes you excited about them? What are you after there?

I don’t know what makes me excited yet. I just have an urge to make landscape works. I can’t really say why, but I think with art-making, it’s probably clever to follow that unknown and see what can be unearthed in the process. I potentially foresee them as another way for me to play with what it means to be an artist. When I was younger, I would never have dreamed of making landscape works; they wouldn’t have interested me as a subject matter. So, personally, I’m intrigued to explore this change in motivation.

The idea began a few years back when I did a cycling trip along the Baltic coastline in Germany, and one night, while walking along a cliff coastal path, I was struck by the view. The Baltic coastline is starkly different from what I’m used to on the Atlantic coast of Ireland. The ocean and surrounding land are flatter and more pictorial, ready to be directly transposed to my woodblock format. I could see it very clearly in terms of a flat image with a foreground, middle ground, and background.

Hopefully, this exploration will also tell me something different about the places I depict. I feel I’ve always gone inward when thinking about making art, and this could be more outward.

Drawing Pöx: With everything we’ve talked about: risk, mystery, learning from difficulties, and the unknown, what is it about drawing that makes you come back to it? Why drawing?

That’s a difficult one to pin down. A lot of reasons and thoughts run through my head as to why. I kind of see everything as drawing. In the simplest sense, it gives me a lot of joy, both doing and seeing other people’s drawings. I see it as a language that everyone speaks to various levels, and I love to see when people have a mature, complex visual language developed.

Now that I think of it, some of my oldest memories are of drawing: my father showing me how to draw perspective or, as a child, drawing with my older brother and putting people standing in long grass, as I couldn’t draw feet.

When I draw, I’m not in complete control of the outcome. I can’t capture likeness in people, and I’ve never drawn a pleasant landscape. With a lot of effort, I can draw objects adequately, but it doesn’t interest me. When I draw, I try to capture an energy or transmit an aggression within the line while pushing the reality of the form. Often, when I finish or look back at a work, the overall scene won’t be that interesting to me, as long as it works visually, but I will find most enjoyment in a line I have captured, the curve of a finger or the bend of a knee.

Also, the drawing tool is always key. At the moment, I’m using quiet, blunt carpenters’ pencils for a heavy line that matches the cuts of the jigsaw power tool, and I like the energy it gives my lines.

I have to mention the experimental theatre company Forced Entertainment. They did a complete version of the works of Shakespeare, which I watched during COVID, using everyday objects from home to play the characters - bottles of tomato ketchup and salt and pepper shakers for a king and queen. This simplification and abstraction of complex characters had a profound influence on how I view making art.

It reinforced something I already feel when I draw: that energy, doubt, and humour are all part of making something real.

Brian O’Shea (b. 1987, Co. Limerick) works under the artist name Ireland 3000. His practice spans drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and performance, often using humour and satire to explore Irish identity and post-colonial history. After several years working as an artist in Berlin, he has recently returned to Ireland to continue his practice.

He studied Fine Art Printmaking at Limerick School of Art and Design (2010) and completed an MFA in Contemporary Art at Edinburgh College of Art (2014). His work has been shown internationally, with recent highlights including the Royal Hibernian Academy, the Royal Scottish Academy, Woolwich Contemporary Print Fair, and the Deutsche Internationale Grafik-Triennale.