A Walk in Time: Christine Metz on Drawing and Presence

“The story doesn't end here; just the pencil will sit back and rest.”

From tiny marks that record events to experiments that merge sound, time, and visual form, Christine Metz’s drawing is a means to tap the blank spots of the world around.

We began this as a casual exchange on Instagram. It unfolded into a conversation that offers insight into Christine’s practice and philosophy.

drawing pöx: Some of your drawing include a row of small signs at the bottom. What do they signify?

Christine Metz: Love your question. The small signs stand for counting time - often in an erratic way. They mark upcoming submission deadlines (which I didn’t always make); geological data of the places where I took the initial photo; the exact time when I considered the drawing done (for the moment); or just the notation of a spontaneous idea.

dp: A story of a story of a story.

CM: I thought about the drawing process the other day, and the idea of story-telling as a different level of intertwining came to my mind. Maybe in the end it’s all about that. Images can stick with us. So do the stories.

dp: I think a lot about what makes a good drawing. An artist’s skill, for one. But skill alone means nothing without a story - I agree. Yet, there’s another ingredient that I can’t quite put my finger on. What is it in your view?

CM: I think I know what you mean, but this one seems quite hard to determine. It could be about the position one takes, which expresses itself through the work. To me, drawing is the attempt to tap the blank spots of the world around - and bring them back blank - while chasing mere beauty.

dp: Before looking into the subject matter of your work, can we stay for a moment on the signs at the bottom of your drawings. They are significant, as they tell the story of your process, rhythm, and perhaps some dilemmas. Is there a unified code? Could one learn this ‘alphabet’ and then decode the footnotes of your drawings?

CM: So far, there’s no intentional code underlying the signs. If not self-explanatory, they can ascertain the erratic way of a thought demanding instant expression - as if to balance and hold at bay the suggested perfectness of the drawing. I also refer to them as marks of tiny events.

dp: How does the medium of drawing influence your perception of what perfectness means? And do you ever find yourself intentionally going in the direction opposite to perfectness?

CM: Not on intention. I try and follow what promises to absorb my attention. That’s mainly the direction. It’s not all about form and style, it’s about what the image evokes and brings forth as an idea. Perfectness then shows, if you will, in a momentary experience, for instance, when you look at the drawing and see and realize - oh, that’s where I want it to go. But as directions can change, I keep redefining perfectness.

dp: Your work spans drawing, photography, and video. What role do photography and video play in how you select and then approach the subjects of your work?

CM: In the beginning stage, photography is the basic artistic tool. Video doesn’t play a role so far. I just most recently added it as another way to look on and explore further the topic of drawing.

So, usually there’s the walk in the open field where the eye strolls around (and ‘always bring your camera’ is what I learned). When I come across a scene with certain features, I take a look through the lens to check the lighting and general appearance and play with the composition. Detached from its own distinct environment by the limiting frame of the camera, the scene turns into a picture while I’m still just looking.

Then, in the moment of recording, the camera distills an excerpt of 1/100 sec out of a timeline of unknown extent and complexity, with each little particle equally depicted at the very same time. And while the photograph implicates distance and abstraction, the original scene becomes fiction. Out of this all, the drawing will built its own reality.

dp: Can I zoom in on something important you mentioned? When you say, “I come across a scene with certain features,” what are the features you look for?

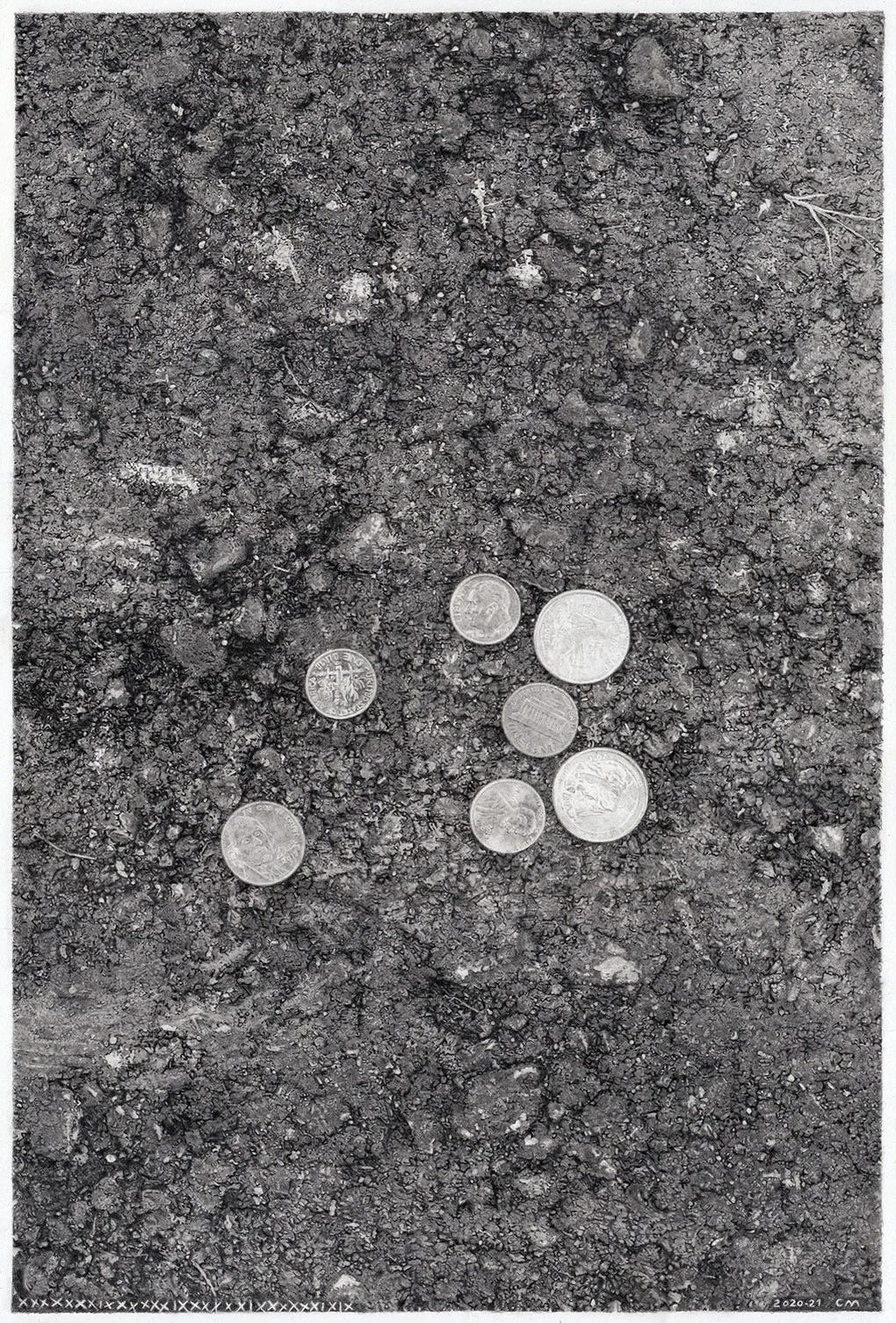

CM: I’m looking for homogeneous structures rather than for wild mixes. I like to have included subtle signs of activity by (somewhat) intelligent sources - from farming equipment guided by humans, to ants - and of influence by natural forces. Hints on cluster formation of any kind are another attribute. Usually I don’t tamper, but there are a few exceptions in the series where I set up and orchestrate the stage, like ‘Asphalt & Coins’.

dp: When I see your work - homogeneous structures, tracks of equipment, cluster formations, asphalt and coins, marks of tiny events - I clearly hear a rhythm. To what extent does your work, in subject and process, imply an acoustic experience?

CM: Awesome question. Indeed the ground drawings, to me, often associate vibrational fields or soundscapes - some of the little side marks even symbolize slow wave patterns underlying the image.

In addition I started experiments to further sift out the connection of sound, sight and the movement of time; this is where elements of video may come into play.

dp: Could you please tell more about these experiments?

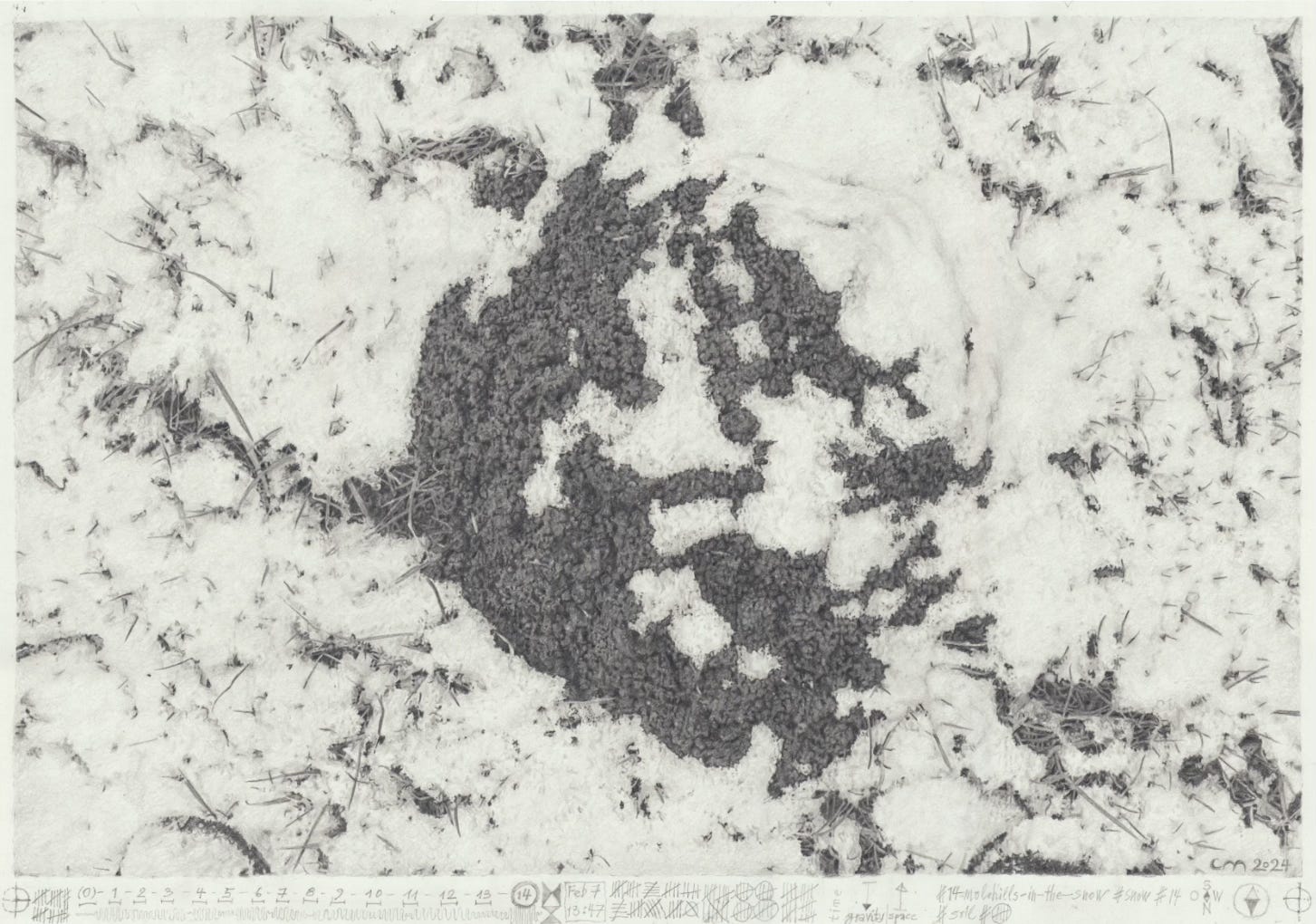

CM: For the current drawing project ‘The Time I Adopted 14 Molehills in the Snow’ I put up 15 (14 plus one) positions on a chromatic scale which I turned into numbers. Each position is defined by three notes played together. The first one marks the chronological order of the molehills in the field; the other two notes are converted numbers from the exact date of when the picture was taken.

For now I’m doing test runs on an old button accordion, which feels like a bold move towards imperfection; which, again, could be the perfect ingredient.

drawing pöx: Fascinating how many facets you work with: music, math, physics/ acoustics, chronology, data transformation, algorithmic processing, performance. Yet, all of this is subordinated to drawing.

So, the ultimate question is: why drawing?

Christine Metz: There’s an appealing straightforwardness to drawing which I can’t resist. By drawing, I get to see better what I’ve been looking at. Even the additional branches of work, somehow, feel like acts of drawing then.

Yet, with or without, bundled within, there’s the story line - starting from the point of when the idea came into being, to the moment when I jump up, declaring the work done. The story doesn’t end here though; just the pencil will sit back and rest.

It’s all about drawing. It’s all about time.

Drawing is a walk in time, capturing presence.

Christine Metz is a German artist whose practice spans drawing, photography, painting, and interdisciplinary experimentation. After earning her diploma in graphic design in 1976, she became an independent artist in 2005, exhibiting extensively and receiving a number of awards, including the 2024 Kunstpreis der Stadt Augsburg. Her works are part of public collections, such as the Kunstsammlungen und Museen Augsburg, and she has participated in prestigious exhibitions across Germany. Christine lives and works in the countryside nearby Augsburg.